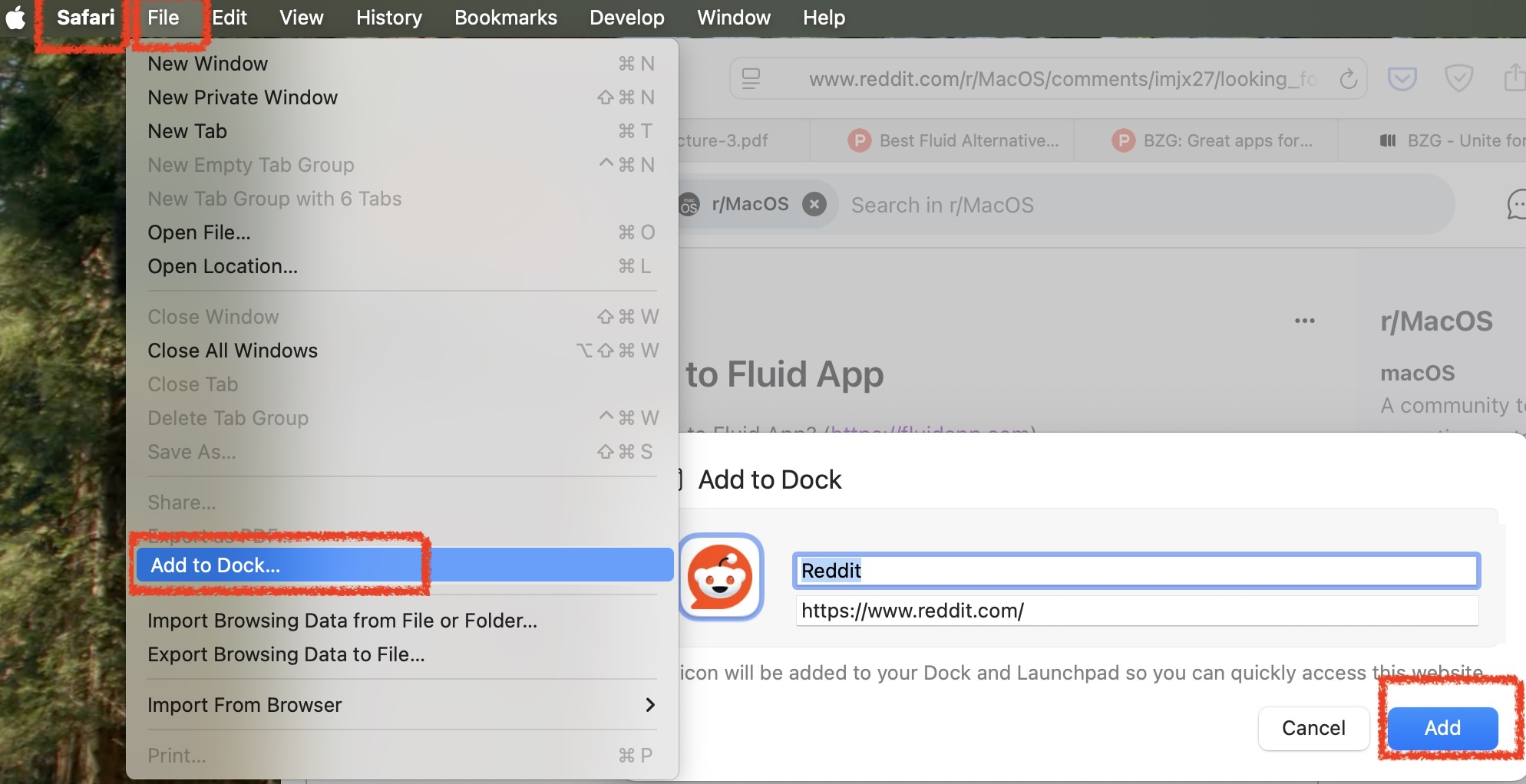

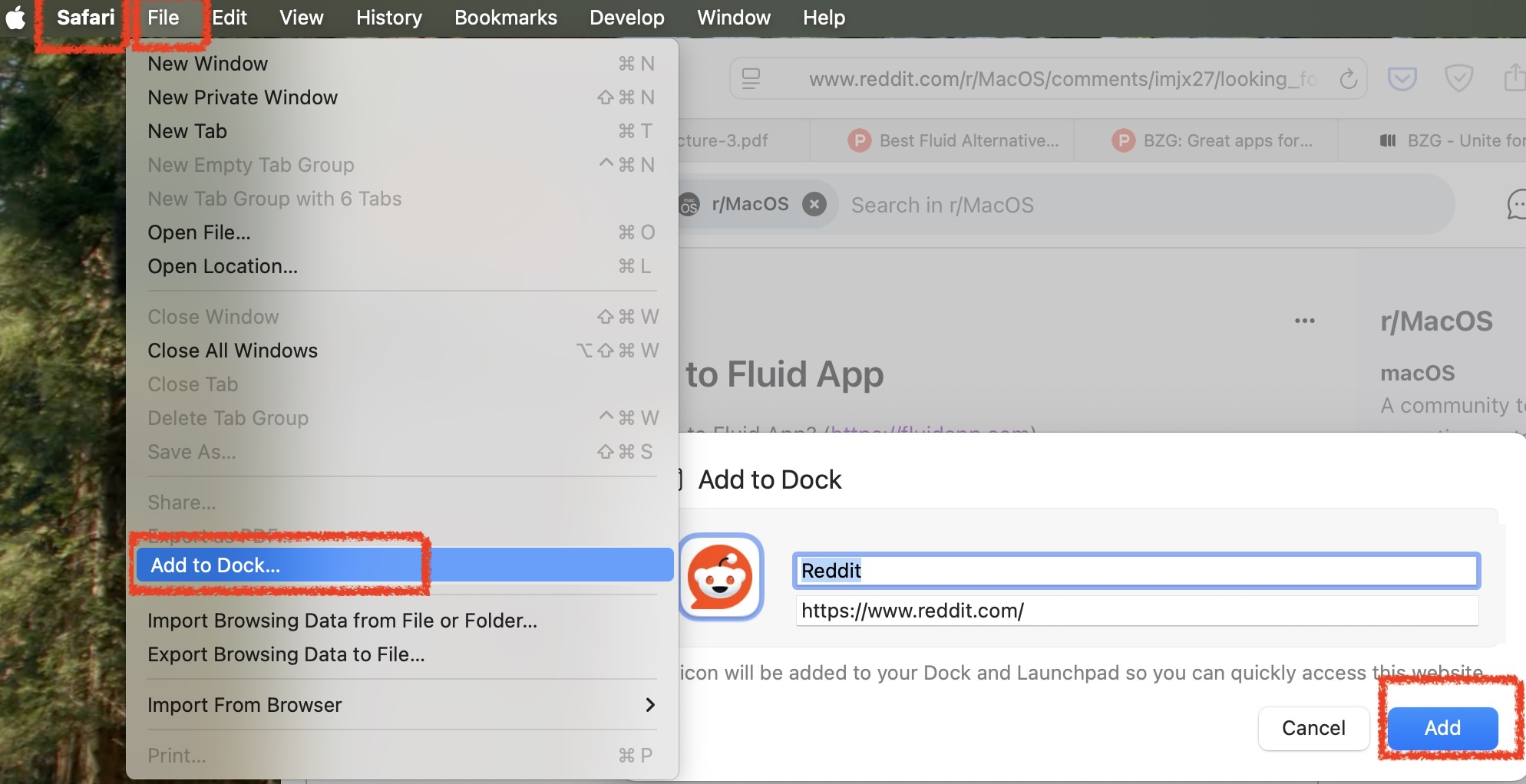

For MacOs users looking for a replacement for Fluid.app that runs on Apple Silicon, it's in the Safari File menu:

Like Fluid.app, it creates an application in your user's ~/Applications directory.

Coffee | Coding | Computers | Church | What does it all mean?

For MacOs users looking for a replacement for Fluid.app that runs on Apple Silicon, it's in the Safari File menu:

Like Fluid.app, it creates an application in your user's ~/Applications directory.

The training of A.I. and machine learning models is, in the technical vocabulary of the field, a problem of credit assignment [1]. The entire achievement of a machine learning training algorithm lies in accurately tracing the myriad miniscule connections — assigning credit — to those features of the input data responsible for achieving each output target in its training data and targets.

It would be ironic then if, tasked with assigning credit to their inputs for their outputs, A.I. modellers should baulk and call that too daunting a challenge.

It is not necessary to achieve a great degree of accuracy, or timeliness or even consistency in assigning credit to content creators and IP holders whose property has been used to train models. A little effort to provide something that is half accurate most of the time would be a helpful start.

It is not necessary to invent a new compensation model, or a new process for registering the interests and contact details of IP owners. The music industry designed and implemented solutions for this problem over a century ago. Without the aid of A.I. Or a computer.

There is such a thing as legalized robbery. For instance, loan sharking used to be legal, but it was still robbery even when it was legal. We prefer to make such things illegal because it is wrong to let those with the will to do so to take advantage of people over whom they have an advantage of, for instance, physical strength.

In commerce, strength is largely financial, partly political. The bigger, better-connected company is immensely more powerful than the individual content creator. Just as with SLAPP cases and with libel laws, the legal battle is too one-sided to even contemplate.

The UK consultation on IP and A.I. provides a unique opportunity to develop and implement a far better vision. The relationship between A.I. developers and IP holders can and should be a positive, mutually beneficial, symbiotic relationship.

A.I. certainly depends, utterly, on IP creators. If the A.I. developer monetizes whilst the IP holder is left with nothing that would be parasitic and destructive[2], not symbiotic. If an algorithm and system is implemented to reasonably share with IP holders fair recompense for their works' contribution to A.I. output, the relationship could be symbiotic, mutually beneficial, and even a virtuous circle of increasing benefit to both. Not to mention the rest of us.

[1] https://www.google.com/search?q=back+propagation+as+an+algorithm+for+credit+assignment

[2] https://www.inet.ox.ac.uk/news/new-study-reveals-impact-of-chatgpt-on-public-knowledge-sharing

The 10 Minute Strategist

Martin Turner, Ingenios Books, 2018

9781980750956

Anyone wanting to be anyone these days needs a good line on strategy. It pretty much defines itself as “the important stuff”.

One route to strategic expertise could be to sign up for business school. A faster, cheaper option might be to get the textbook. Mintzberg, Ahlstrand & Lampel’s “Strategy Safari” could lead you, in 400 pages, through Ten Schools of Strategy and explain what each one offers, with its strengths and weaknesses.

Or—for those whose goal is to become very good at forming strategies, instead of at writing essays—there is Martin Turner’s The 10 Minute Strategist.

The book uses Mintzberg’s ten schools as ten angles on strategy. It scores over the older more pedestrian work in two important respects. First, it is a fraction of the size, readable in a few hours. And secondly, it is immediately usable. Its notable tactic is showing you how to deploy each school as a strategic question, together with an appropriate tool or framework to explore that question and evaluate candidate answers. Equipped with this, you can use each strategy school to explore the challenges you face from the point of view, and using the strengths, that each one offers.

The result is outstandingly well-rounded and practicable. Instead of being strategically limited, knowing only one or two ideas of what a strategy is, having ten approaches at your finger-tips enables you to rapidly pick out the angles most important to your current situation, and yet still be confident you have considered the other angles too. Your risk of shipwreck or failure further down the line, from surprises your strategic approach didn’t consider, is cut exponentially.

To save you some hours in the library, the ten schools of strategy are the power school, the entrepreneurial, the cultural, the… well, find the others in the book. Meanwhile, consider instead Turner’s questions that represent each school. Turner’s ten strategic questions are:

⁃ What’s the situation?

⁃ What’s the big idea?

⁃ Do we dare?

⁃ Who is with us?

⁃ What are we good at?

⁃ What are we doing that’s different and how will we take people with us?

⁃ What actions do we need to take in what order?

⁃ How will we get better as we go?

⁃ How are things arranged?

⁃ How will this strategy change us?

I typed those out from memory, because The 10 Minute Strategist includes a handy 10-letter mnemonic — “STRATEGIST” — for remembering the 10 schools and the corresponding question. Situation, Thinking, Resolve, Allies, Tactics, Embedding, Gameplan, Improvement, Systems, Transformation.

This is a second notable feature of the book. The medical profession (Turner has been amongst other things an NHS trust director), uses mnemonics pervasively to memorize and recall key headings for hundreds of conditions on the spot. The 10 Minute Strategist does the same. For each question and its associated tool(s), you have some kind of mnemonic or memorisable plan for how to explore it, or to evaluate what you’ve got so far.

Expert thinkers are recognisable by their knowing, within their area, just the right questions to ask, and knowing what good answers looks like. So this approach, using questions plus a tool or framework for developing and evaluating candidate answers, strikes me as fundamentally correct. To be the person able to lead your team to find the right strategy, you want to have the right questions, and an idea of what good answers look like, all on the tip of your tongue.

After a discussion of how and why strategies fail, the meat of the book is then a walkthrough of how to use each of these questions, and what their associated viewpoints offer to you, the budding strategist.

Some strategic tools, such as SWOT, are well known. Turner offers critique and history (did you know that the consultancy that invented SWOT stopped using it?) and suggests for each school the tools or framework with which you can most effectively deploy it.

Throughout, Turner uses examples or guidelines at three timescales. One running example demands a strategy within 10 minutes, because lives are at immediate risk. The second is guidance on how to lead people through a two-day long strategy workshop. The third is how to extend that into strategy formation in the context of very large very complex organisations, with entrenched interests and fiefdoms.

The 10-minute timescale —strategy for a single day— may surprise you. Yet it is the key idea that can help you become a strategist! At very, very best you could get two chances in your lifetime to develop a large-scale strategy. That’s not even enough practice for you to get past the “newbie” level of mistakes. This is surely one reason why large strategies are more famous for their failures than their successes.

Turner’s proposition then, is that by determined practice in applying his ten strategic questions right now, on your present daily challenges, you can become, even early in life, the kind of thinker who when faced with the big challenges has already mastered the skills of how to find and develop winning strategies.

This is the heart of what the book offers. A guide for you personally to learn, to grow, and to become a successful, reliable, strategist.

TL;DR: Blazor Cascading Parameters are matched by Type not necessarily by Name. The simplest solution is to declare the Parameter type as Delegate. If you need to distinguish more than one delegate cascading parameter, then declare a named delegate type (that's a one-liner in C#) and use that as the parameter type.

You want to pass a callback as a cascading parameter. You try passing a lambda, or possibly a method, and create a CascadingParameter property, with matching name, of type Action or Func<...> or similar, to receive it. But the cascading parameter is always set to null.

Cascading parameters are matched up by Type, not by name, and who knows what the compiled type of a lambda will be? The C# reference tells you that that lambdas can be converted to delegates or expression trees but 'can be converted to' isn't good enough for matching up by Type.

Declare your parameter to be of type Delegate. Most callable things in C# are of type Delegate.

// Declaration in the child component

[CascadingParameter]public Delegate OnChange { get; set; }

// Use in the child component. The null is what DynamicInvoke requires for 'no parameters'

OnChange.DynamicInvoke(null);

# In the parent container

<CascadingValue Value="StateHasChanged" >If you must distinguish between several Delegate parameters, or just want to better express intent in your code, you can define a named delegate:

public delegate void StateHasChangedHook();and use that as the Type of your CascadingParameter:

// Declaration in the child component

[CascadingParameter]public StateHasChangedHook OnChange { get; set; }

// Use in the child component is slightly simpler

OnChange();

# In the parent container

<CascadingValue Value="(StateHasChangedHook)this.StateHasChanged" >When you use named delegates, you can invoke them with onChange() syntax instead of .Invoke() or DynamicInvoke(null).

You can inspect what was set in the child parameter

log.LogDebug("OnChange was set {OnChange}.MethodInfo={MethodInfo}",OnChange,OnChange?.GetMethodInfo())Recall that Action<> and Func<> are themselves named delegates, not types. They are declared in the System assembly as for instance: public delegate void Action<in T>(T obj)